And Then There Were The Victorians - A Short History of Libraries - Part III

- Lynne Shelby

- Oct 18, 2021

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 28, 2023

From the fall of the Roman Empire, through the Dark Ages and the Middle Ages, to the Renaissance, the monks of Northern Europe could be found in their monastery’s scriptoria copying and illuminating manuscripts, preserving the knowledge of the ancient world as well as more recently written books, but with the religious upheavals of the Reformation in the sixteenth century CE, and the political upheavals that followed, this peaceful book-loving monastic existence came to an abrupt end.

In England, 1536 – 1541 saw Henry VIII taking time out from executing Anne Boleyn and marrying Jane Seymour to dissolve the monasteries (and redirect their incomes to the Crown). The destruction and looting of the religious houses and the selling off of their lands, also saw the dispersal – and often the destruction – of the contents of their libraries, with some volumes being torn apart for their valuable bindings and others being sold by the cartload to folk who rather than read them used them to scour candlesticks or clean boots. Of the six hundred books known to have been in the library of Worcester Priory, only six have survived to today.

With the destruction of monastic libraries many books were lost for all time, but during the reign of Elizabeth I, the Queen’s principle advisor, William Cecil, and her Archbishop of Canterbury, Matthew Parker, along with private collectors such as Sir Robert Cotton and Sir Thomas Bodley, sought out the scattered manuscripts to form their own libraries. Their collections eventually became the basis of libraries that are very well-known today – Parker’s went to the library at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Cotton’s eventually became part of the British Library (which still holds his collection), while Bodley’s formed the Bodleian Library at Oxford, open to ‘the whole republic of the learned.’

The Francis Trigge Chained Library of St Fulfrum’s Church, Grantham, founded in 1598, is considered a direct ‘ancestor’ of public libraries as we know them today, since, unusually for the sixteenth century, its founder intended it for the use of the inhabitants of the town rather than the members of a particular institution such as a school or university. Originally its books were chained to shelves, and eighty-two chains can still be seen today. Interestingly, and uniquely in the era of the Reformation, the volumes in the Chained Library reflected both sides of the religious argument. Not unsurprisingly, most libraries at the time held books that argued for the beliefs of whoever founded the collection.

Over in continental Europe, libraries in the sixteenth century had mixed fortunes. Martin Luther, the instigator of the Reformation, was very much a bibliophile, and wrote a letter to every German town insisting that they should all set up libraries – there are libraries in Hamburg and Augsburg that date from this time – but the Thirty Years War that ravaged Europe between 1618 and 1648 saw books carried off as plunder from one library to enrich another. (Yes, King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, it’s you and the library you founded at Uppsala we’re talking about!)

Meanwhile, in China, the Tiyani Ge (Tiyani Chamber) library was founded in 1561 - and is still in existence today. In its prime, it held a collection of 70,000 antique books.

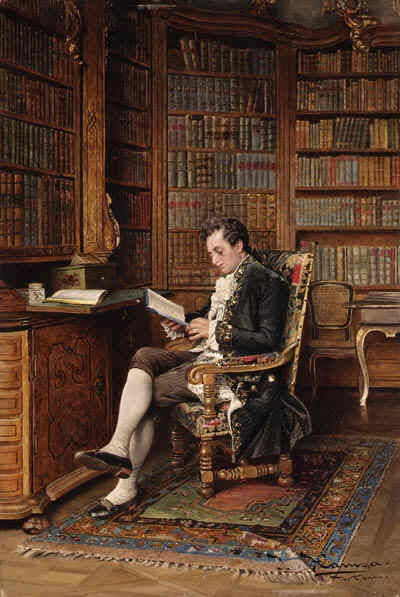

By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in Europe and North America, book collecting had become more widespread, and many fine private libraries were to become the basis of today’s great national collections, such as the Library of Congress in Washington, USA.

There is some doubt as to whether the original collectors put together their libraries for the love of books or as a means of showing off their wealth – and the confiscation and distribution into depot literraires of aristocratic libraries by bibliophilic French Revolutionaries may not have been done entirely in the spirit of scholarship – but nevertheless so many important libraries were founded that this era is known as the Golden Age of Libraries.

Most of them, however, weren’t open to anyone who fancied browsing the shelves, but restricted to scholars or institutions, Cheltham’s library in Manchester – established in 1653 under the will of Humphrey Cheltham for ‘the sons of honest, industrious and [sic] painful parents’ – being one of the notable exceptions.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, there were still virtually no public libraries as we understand them, but subscription libraries supplying serious books to those who could afford the high membership fees, and commercial circulating libraries, operating out of shops, supplying the rising middle classes with novels became increasingly popular – despite fears that female readers were unable to differentiate between the more sensational elements of fiction and real life!

Skip forward half a century, and it was the Victorians, with their belief in self-improvement – particularly for the unfortunate ‘lower classes’ in need of distraction from drink – who, when they weren’t inventing the Industrial Revolution, fostered the idea of establishing community libraries for all funded at public expense. Eventually, after some opposition from the less philanthropically minded, this resulted in Parliament passing the 1850 Public Libraries Act, enabling taxes to be raised to fund public libraries.

By 1877, seventy-five cities in England had public libraries, by 1900, there were three hundred.

This was the start of public libraries as we know them today.

Comments